- Screen Colours:

- Normal

- Black & Yellow

What is an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC)?

What is an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC)?

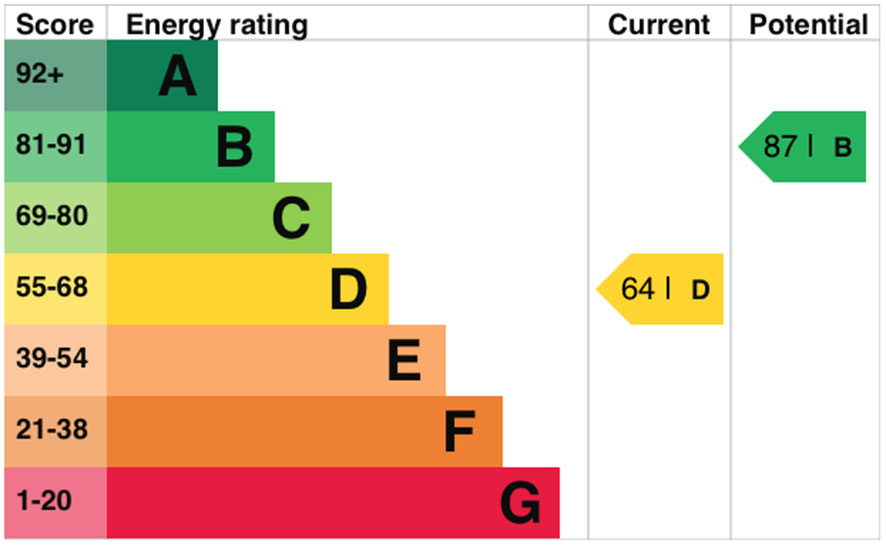

Essentially, it is a guide to the the energy efficiency of a property, produced by an independent accredited assessor. It shows not only the current efficiency but also the potential efficiency on completion of a range of improvements. EPCs were introduced in October 2008, under the general umbrella of the Minimum Energy Efficiency Standard – now all part of the clean Growth Strategy.

An EPC is a legal requirement when a home is built, sold or let. This is when they are usually seen, but they can be commissioned at any time. There is a narrow range of exemptions to the requirement, the most relevant being for listed buildings. While an EPC is not required before a listed building can be marketed, there is no bar to one being commissioned. Typically, an EPC might cost between £50 and £75. It is valid for ten years, and is centrally registered. They can be found at http://www.gov.uk/find-energy-certificate; helpfully, those properties with EPCs are grouped by post-code order, to make comparisons simpler.

How is an EPC prepared?

The assessor will inspect the loft, walls, windows, floor, heating and lighting and enter the details and likely age into a computer programme. The programme will then produce a graph, a score for each element, and a total score. A rating of A, with a score of 92+, is the most efficient, G, 1-29, the least efficient. For England and Wales, the average energy rating is D and the score 60.

The inspection cannot, within its limitations, be wholly accurate. For example, the assessor must make have evidence as to whether or not a flat roof is insulated; an older roof is probably not, but may have had insulation added when last refelted. Failing evidence, the programme defaults to the Building Regulations standard based on the age of the roof. A fairly standard assumption is that a solid floor is not insulated; that is likely to be correct in almost every case. Again, the assessor is required to make a judgement as to the age of replacement windows; not always easy. In particular, the condition of the element being reported on is not assessed.

Potential energy efficiency

The certificate also gives recommendations on how to improve the property's energy efficiency, with very approximate installation costs. For a small mid-terrace late Victorian bungalow, the estimated annual saving in energy costs through insulating the 9 inch solid walls is given as £57; the cost of the work is put at between £4,000 and £14,000. The cost of putting in low energy lighting was given as £25, against an annual saving in energy costs of £35. This property had good loft insulation, modern double glazed windows and new gas central heating, and assumed flat roof insulation (a brave call, having regard to the age of the roof), but was rated D.

The costs and savings are to be treated as rough guides only, but they are useful in prioritising energy-saving measures. Importantly, the savings for each measure assume that all the previous measures are in place – i.e. they are sequential. Returning to the graph, the Potential score and grade is what could be achieved by incorporating all the recommended improvements, including solar photovoltaic panels. For the bungalow previously referred to, the yearly energy savings total £534, against a mid-range cost of £23,525. The return of some 2.7% is not exciting, but a better return could be achieved by careful selection of the most worthwhile improvements.

Discussion

Within their limitations, EPCs are clearly a valuable tool in the search for energy efficiency. The certificate itself is clearly set out and straightforward in its guidance. It also has within it some very useful links to sites offering help with energy-saving grants, renewable heat incentive payments etc. Some of the installation costs given may be too broad, but are indicative of possible costs within a necessarily wide range of settings.

In one sector EPCs will soon have a considerable effect. Under current legislation, properties can only be rented out if they have an energy rating of E or above. That is to be increased to a rating of C or above, probably with effect from 2025 for new lettings and 2030 for existing lettings. The bulk of the private rented sector stock is thought to be of solid-wall construction, and therefore needing a proportionately higher cost to bring up to the required standard. Some 3.4 million properties in the private rented sector are believed to have EPCs of D or below.

The reasons for the change are not difficult to see. The average energy costs for a C-rated home are reckoned to be £657 a year; for E that figure rises to £1,425. For a G home, the amount is £3,105. Currently, landlords may seek a temporary exemption, valid for five years, where the costs are beyond practical, cost-effective and affordable; there is a cap of £3,500 for the landlord's costs. That seems a modest sum , with house prices at their current levels. The detailed provisions are complicated and outside the scope of this paper, and there is clearly scope for litigation.

The suggestion is that over time the private rented sector could shrink, as landlords sell properties rather than incur the considerable costs of upgrading (without necessarily seeing a commensurate increase in rents). But an energy-efficient home is cheaper to heat, and first-time buyers could find themselves with more choice and possibly more attractive prices. The market will be interesting.

A future paper will look in more detail at the alternatives for improving energy efficiency.

See our Links page for useful links.

Note: Ipswich Building Preservation Trust isn’t able to give direct advice, but aims to start a conversation, inform people of current ideas with arguments for and against.